“Witches of Essex”: What the Sky Documentary Gets Right — and What Everyone Is Still Missing

- Sinead Spearing

- Dec 10, 2025

- 4 min read

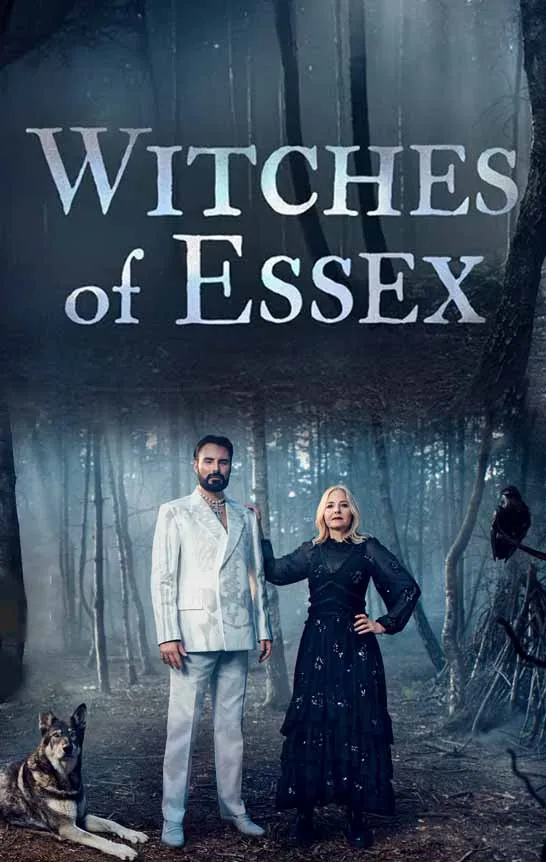

I began watching Witches of Essex with a quiet sense of inevitability. These stories have followed me for years — the women pulled from the margins of English history, branded “witches” because no other word seemed to serve the needs of fear or authority. Essex in particular has always felt close, not only as a landscape but as a long echoing corridor of voices: healers, widows, wise women, mothers, scapegoats. So when the new documentary series arrived on Sky HISTORY, presented by Rylan Clark and Professor Alice Roberts, I knew I would watch it with both anticipation and that familiar ache — the ache of knowing how these stories usually go wrong, or shallow, or noisy when what they require is tenderness.

The series takes us back to the mid–sixteenth century, beginning with the 1566 case of Agnes Waterhouse and moving through to the 1582 St Osyth trials, before descending into the bleak machinery of Matthew Hopkins’ “witchfinding” campaign. It follows the archival trail, calls in historians and legal experts, stages recreations, and attempts to illuminate the women who suffered beneath the weight of accusation.

There is something undeniably moving in the way the presenters sift through court records and try to imagine the faces behind the ink. Roberts brings a sober clarity; Rylan brings a kind of accessible witness-energy. For many viewers, this will be their first encounter with England’s own witch hunts — a part of our history still strangely under-taught.

And yet, as I watched, I found myself experiencing that familiar doubleness: gratitude that these women are being spoken of at all, and frustration that the deeper truth remains elusive. Many reviews have already caught this tension — The Guardian called the series “moving, if slight,” noting that it gestures at misogyny without fully unpicking it and later criticised the uneasy mix of sombre history and near-Halloween theatrics. The dramatic reconstructions can feel jarring; the tone sometimes floats between reverence and spectacle, as if the programme can’t quite decide whether it wants to mourn or entertain.

Yet there are moments — rare but important — where the veneer slips and something more honest emerges. Rylan says at one point, almost offhand but with startling clarity, that a woman could be accused for the crime of being disliked, or for the crime of having a birthmark, or simply for the crime of existing at the wrong time in the wrong place. There it is. That one sentence sits right at the heart of my own work: these women were not witches. They were never witches. They were convenient containers for fear, for grief, for suspicion, for the instability of communities pushed to breaking point by poverty, famine, religious turbulence and male authority desperate to reassert its grip.

This is the place where the documentary brushes against something vital, and then — frustratingly — moves on. It shows the accusations, but not the women in their wholeness. It tells us what happened to them, but not who they were. We hear their charges but not their knowledge. And for someone like me, who has spent years studying early English medicine, translating Old English remedies, and tracing the long shadow of women’s healing traditions, this feels like a missed opportunity. What made a “cunning woman” valuable to a village? What was the herbal, psychological, and spiritual skillset that so many relied upon, right up until they decided to turn on her? What is the lived texture of folk medicine — the earth under the nails, the hum of botanical knowledge, the quiet authority of a woman who knew how to bring life into the world, ease pain, soothe illness, and mediate communal tensions?

These are the questions the series skirts but never sinks its hands into. And perhaps that is its remit — mainstream television often stops at the scaffolding, unsure how to handle the deeper human story without drifting into romance or anachronism. But the cost of that restraint is that the so-called “witches” remain primarily as victims, not as practitioners, not as agents, not as brilliant, complex women navigating a society that both depended on them and feared them.

Still, I find myself oddly grateful that the programme exists. It is imperfect, uneven, and sometimes overly theatrical, but it opens a door. It asks viewers to reconsider the received idea of the witch — not as a spell-casting villain, but as a neighbour, a healer, a poor woman with no social shield. It acknowledges, even if fleetingly, that these accusations were almost never about magic. They were about power.

And perhaps — just perhaps — this is where those of us working more deeply with this history can step in. My own research and my studies of Old English medical texts, seek to peel back the centuries of slander and restore these women to their rightful place: as early physicians, as guardians of psycho-social healing methods, as women whose knowledge was so sophisticated that it had to be crushed in order for later patriarchal medicine to rise.

Watching Witches of Essex, I felt again the quiet vow that threads through all my work: to remember them not as “witches,” but as women — brilliant, misunderstood, necessary women — who deserved honour, not horror. If this series encourages even a handful of viewers to sense that truth, to seek it, to question what they’ve been taught, then perhaps it has done its job.

For the rest, we can go deeper. And I intend to.

Comments